This article is prepared based on official Ferrari Youtube channel video mentioned at the end of the article

Today, we’re going to take a brief look at moments in Ferrari’s design history—key works of art that have defined the Prancing Horse’s shape DNA to this day and will continue to influence it in the years ahead. At the center of this reflection is Carlo Palazzani, Head of Pilot Design Projects at Ferrari. With a career rooted in both Pininfarina and Maranello, Carlo has become one of Ferrari’s most thoughtful design voices—balancing innovation with legacy. He approaches design not as surface treatment, but as the art of transforming engineering into emotional form. Through his eyes, each Ferrari is not just a car, but a sculptural response to function, history, and the future.

For Carlo Palazzani, Ferrari design is not a matter of nostalgia—it’s an evolving dialogue between technology, emotion, and legacy. Tracing the lineage from the revolutionary Dino 206 GT to the sculptural density of LaFerrari, this reflections reveal a deep commitment to turning complexity into clarity. This is not merely a history of beautiful cars, but a journey through the ideas, tensions, and breakthroughs that shaped them. Through his eyes, each model becomes a chapter in a living philosophy—one where form follows performance, and beauty is always earned.

The GTO marked the beginning of the great legacy supercars. Before continuing a journey full of meaning and discovery, Carlo Palazzani paused to reflect on the mission of design at Ferrari. For him, good design is the ability to translate technical complexity into elegant clarity. It’s a principle he always returned to—where truth emerges through form, not decoration. As he often said: “Good design is the ability to transform technical complexity into elegant clarity.”

This idea remained alive through the 20th century, passed from Ferrari to Pininfarina and now preserved in the Maranello Style Center. To Carlo, it became a pillar—an ever-present force behind every line drawn and every surface sculpted.

Carlo considered the GTO the synthesis of a revolution that began in 1967. The Dino 206 GT introduced the mid-rear-engine layout to the market—an idea Enzo Ferrari initially resisted. For Enzo, the 12-cylinder front-engine layout was the Ferrari identity. But market demands and performance objectives pushed a new direction. The Dino, designed by Aldo Brovarone at Pininfarina, fascinated Carlo, particularly in how its layout reshaped the proportions of a Ferrari road car.

In 1968, Leonardo Fioravanti, Pininfarina’s style director, introduced the Ferrari P6. It offered a glimpse of a new Ferrari aesthetic—defined by the wedge. While Lamborghini pioneered the wedge with the Countach, Carlo admired how Ferrari gave the form its own voice: purposeful, sharp, and architectural. The idea of the wedge took on a unique Ferrari character.

When the Modulo debuted in Paris in 1970, it proved to Carlo that anything was possible with a rear-mid engine layout. Its space-age volumes and graphic purity left a permanent impression on Ferrari’s visual DNA—and on Carlo’s personal trajectory as a designer.

By 1984, the evolution led to the 288 GTO. Carlo saw this car as the moment when Ferrari’s rear-engined berlinettas found their definitive proportions: long front overhang, compact cabin pushed forward, tight rear. These characteristics, to him, became the architecture of all that followed.

The 288 GTO also introduced the “Coca-Cola” shape—a curvaceous midsection that tightened the waist between muscular fenders. Carlo returned to this form again and again. He never replicated it but always reinterpreted it. In the Daytona SP3, the Vespa waistline was his tribute to it. On the TDF, the triple louvers were drawn from the same source. These references, skillfully integrated, made the TDF one of the most desirable Ferraris of its time.

The 288 left a deeper, more personal imprint on Carlo Palazzani. Born in 1980, he was just four when it was released. It competed for his imagination alongside the Testarossa, creating what he called a “spiritual crisis.” But the 288 became his visual north star. Every project he touched later carried its fingerprint: low headlights, horizontal mouth, intense but restrained proportions.

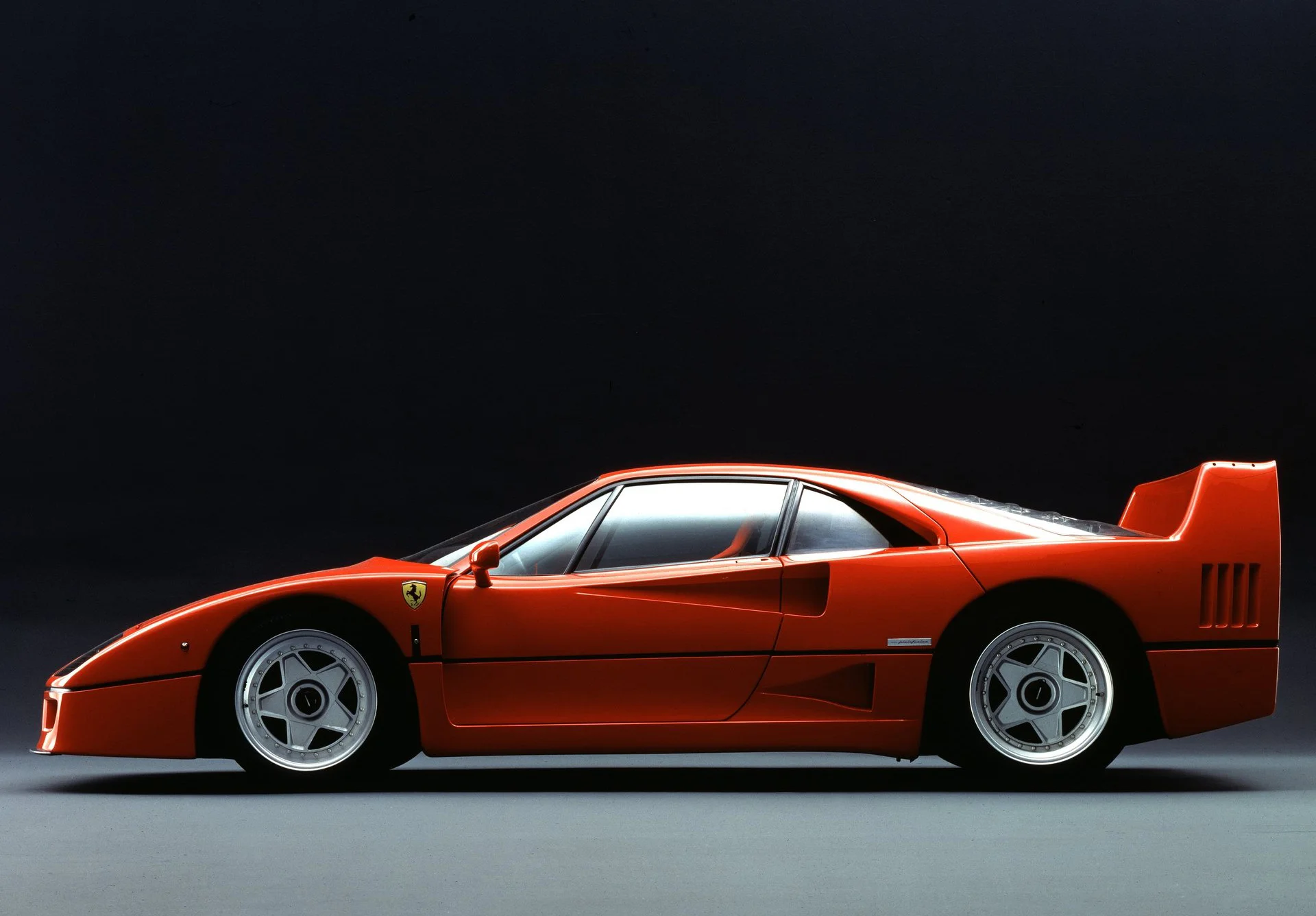

Then came the summer of 1986. The F40. The project, led by Ferrari, Michelotto, engineer Materazzi, and Pininfarina, started as a restyling of the 288 GTO Evoluzione. Carlo remembered conversations with Piero Camardella, who described the project as difficult—rough, rushed, yet full of potential.

Those original sketches from the heat of that summer told the story. The desire to harmonize existed, but the conditions were technical and demanding. Carlo often pointed to a particular sketch by Aldo Brovarone—where the front had already moved forward, and the rear wing was taking shape. Most of the car, he noted, was already complete in essence.

Then came the wind tunnel. It gave the F40 its signature. Carlo admired how it wasn’t just styled—it was engineered into being. The flaps, eight in total, were carefully considered. Camardella had wanted them aligned. Despite their asymmetry, Carlo saw harmony in the functional rhythm.

The front end became one of Carlo’s favorite studies: a single tensioned surface, eyes filled with melancholy, a smiling mouth—delivering a dualism that was both brutal and beautiful. The Coca-Cola shape returned, this time sharper and more muscular, but still rooted in sensuality.

The rear told a truth that moved him. He recalled seeing an F40 on the street, its rear mesh revealing everything. The transparency, the exposed mechanics—honest, uncompromising.

The 1990s arrived, and with them, a softer design culture. Technology began to feel more human. Products like the Miata or iMac embodied this shift. Ferrari followed suit with the F50. Camardella’s early sketches reflected this sensitivity—organic forms, refined flow. Though rooted in the F40, the F50 had a new character. Formula 1 began shaping Ferrari’s design instincts. Carlo saw this era as the first time F1 aerodynamics directly influenced road car sculpture.

Camardella left midway through the F50’s development. Others carried it to completion. To Carlo, its reception was muted, not due to a lack of merit, but because it stood too close to its predecessor. As Matteo once said, the F50 remained too tied to the F40 in theme. Ferrari learned from this: never echo a legend too directly.

Still, the F50 aged gracefully. Carlo, originally a GTO-F40 purist, eventually came to admire its proportions. The headlights reminded him of the 275 GTB—open, friendly, elevated. He even referred to them as “reassuring.” Over time, the F50’s soft surfaces and elevated forms helped transition Ferrari into the 21st century. Its design language bled into the 550 Maranello. Carlo often described the F50’s rear as possibly the most beautiful Ferrari tail ever made. The rawness of the F40 found new balance here. That, to him, was the essence of “Ferrariness.”

Then came the Enzo. Having spent a decade at Pininfarina, Carlo knew the inside story well. While Ken Okuyama received most public recognition, Carlo respected the contributions of others—especially Giovanni Piccardo. In 1999, Piccardo visited Maranello, saw John Barnard’s 640 F1 drawings, and envisioned a road-going formula car wrapped in a fairing.

To Carlo, the Enzo was a plane—a machine outside of time. He once watched one glide through the cobbled streets of Rome, and the image stayed with him. Its proportions were extreme: a front long and taut, fenders floating independently, the cabin compact and pushed forward. The early models mirrored the 640’s silhouette. Ken’s bold, full-scale sketches gave the car its unmistakable presence.

Even now, the Enzo still feels contemporary. Carlo admired how the rear anticipated a wing that never came—regulations changed, but the design adapted. Active aerodynamics took over. The result? Dynamic sculpture that always looked in motion.

LaFerrari became the ultimate test of Carlo’s design philosophy. Here, density defined everything. Engineers delivered extremes in data; the challenge was to create clarity through line. Using aerodynamic flow maps, 3D modeling, and pure sketching, Carlo helped guide a process of deep collaboration. These tools enabled real-time negotiation between design and performance.

Designing LaFerrari required him to explore abstraction—the Möbius strip, Anish Kapoor’s seamless forms, imagined flying bodies. Then, he always returned to the sketchbook. For Carlo, that hand-to-head connection was sacred. It sharpened instinct, forged excellence.

He referenced the shark nose of the 156 Dino, the dual transparent mouth as a signature. Modelers, in turn, refined the car’s soul. Their experience polished every reflection. Once surfaces were scanned and finalized, the design stood complete—a promise kept.

Creating a Ferrari today, Carlo often said, was monumental. So many inputs. So many voices. With colleagues like Matteo and Andrea, creative tension was common. But from that tension, balance emerged. And from balance—beauty.

That is how Carlo Palazzani sees Ferrari. Not as static history, but as a constant act of translation—from technology to truth, from legacy to emotion. One masterpiece at a time.

This article is prepared based on official Ferrari Youtube channel video https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qWwKPdBo9l4&t=4590s